She’s a literary icon whose accolades include a 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature. For the African American reader who has been glued to her books since 1970, starting with her poignant debut novel The Bluest Eye, this doc is an opportunity to see how the pieces of Morrison’s life have made her whole.

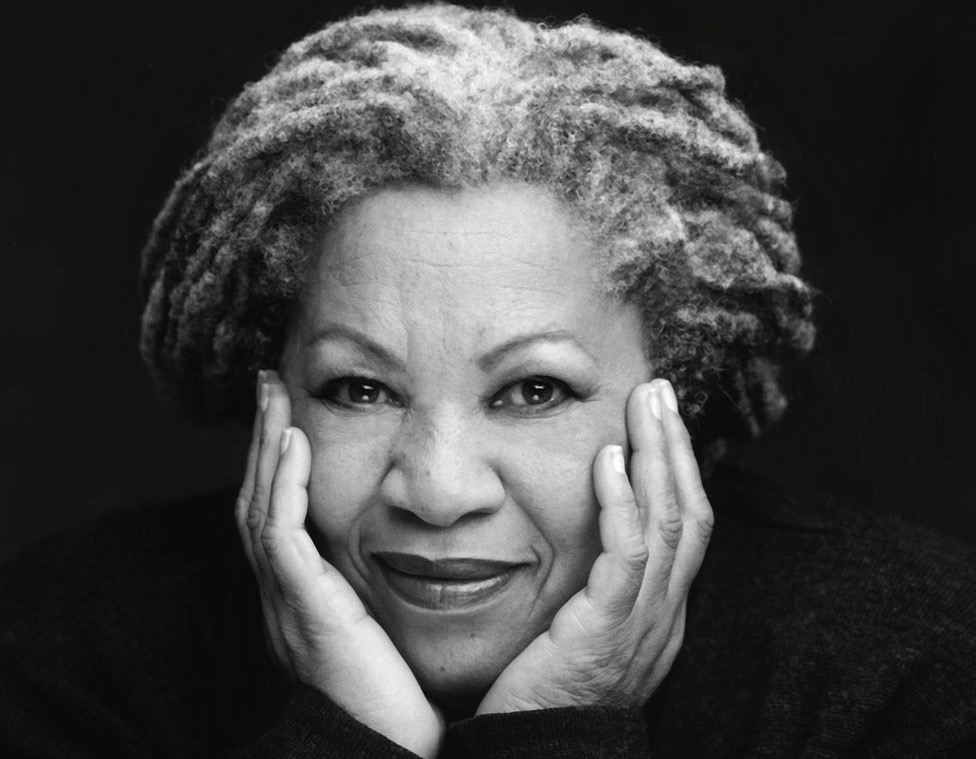

For those who came to the party late, this recounting of her evolution explains why, when you see a photo of this amazingly young looking 88-year-old, you can discern a certain brilliance hiding in her eyes, an extreme intelligence behind her disarming smile and a stately aura that is somewhere between that of queen and goddess.

One of the most interesting facts in this bio is that Morrison grew up in Lorain, Ohio, a multicultural immigrant town. Even if people didn’t fraternize much with each other in their homes (and that’s only a guess), shopping, town activities and education threw everyone into the same mix. It’s no surprise that when Morrison entered Howard University and confronted segregation in The South that her perspective on life and race changed dramatically. Her evolution on the subject matter is as interesting to watch as her development as a writer.

When she helped school her white editors on the power of her works and viewpoints on African American culture and experiences, she faced the same challenge that many African Americans encounter when dealing with their white counterparts in business, education, politics, etc. Resistance. As she recounts her experiences, Morrison is poised, resolved and reflective. Somewhat akin to an intelligent philosopher or an academic who patiently teaches a class of inquisitive but slow-learning freshmen.

You discover that she started her editing career as a divorced woman with two young boys, but that is about as deep as the footage goes into exploring her personal life. There are glimpses of Morrison behind closed doors, but nothing explicit, controversial or negative. In that way, this doc feels a bit like a promotional reel, which isn’t a detriment, as any details about Morrison are better than none.

Many of her books come up for discussion: Sula (1971), about a deep female friendship, Song of Solomon (1977), perhaps her best piece of storytelling and certainly her most accessible novel and winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. The ‘80s brought Tar Baby (1981), then the somewhat controversial Beloved (1987), which was turned into a film by Oprah Winfrey, whose Book Club and TV show catapulted Morrison into the consciousness of middle America, or at least those who liked to read.

Still, some of her most illuminating thoughts on race were established in The Bluest Eye. This profound novel chronicles the indoctrination of blacks into a white society to the point that self-esteem is tied to white characteristics that blacks don’t have, like blue eyes. Among other revelations in the book, her astute analysis of cultural manipulation that results in low self-esteem is enlightening.

One source of inspiration for the book came from a jarring encounter with an African American friend. Friend: “I don’t believe in God,” Morrison: “Why?” Friend: “Because I’ve been praying for blues eyes for two years and he didn’t give me his.” If that doesn’t rip your heart out and send a clear message about the cruelty of systematic or unintended racism, nothing will.

There are other incidents reported by Morrison that influenced the shaping of her values, views and desire to write books that could change social mores: Her mother made her erase the word FU– off a sidewalk. Why? “Because words have power.” Rather than keep this and other life lessons to herself, Morrison has shared them consistently in novels, essays, lectures at universities, on TV—wherever a platform could assist her: “The only way I can own what I know is to write.”

The writer-turned-editor-turned-novelist stood up to anyone who had a misconception about black literature and who it was written for or how it should be received. She ripped preconceived notions and fallacies apart by revealing the problem: “The assumption is that the reader is a white person.” She put that misguided viewpoint to bed.

Morrison seems at peace with the battles she’s fought—or that were fought for her. Her history growing up in an integrated city undoubtedly forged her persona. Even with that multicultural background raising her consciousness, she had to disavow some of the misconceptions she was getting from home, to become the person she is today: “My father thought all white people were unredeemable.” Throughout her career, she has been championed and loved by both blacks and whites.

Director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders (The Black List: Volumes One to Three) pulls together an interesting group of fans and friends who have witnessed Morrison’s rise and have praised her: Decades-long editor Robert Gottlieb; fellow novelist Walter Mosley; activist Angela Davis; and essayist Fran Lebowitz. There are also glimpses of legendary poet Sonia Sanchez, Winfrey and others.

The archival footage, photos and newly shot interviews on-view look clear (Graham Willoughby cinematographer), neatly pulled together (Johanna Giebelhaus, editor) and are properly highlighted by a beguiling score (Kathryn Bostic, composer).

The first documentary to genuinely explore Toni Morrison’s ascendance into the upper pantheon of the literary world does a nice job revealing her wonderful persona, uncovering her backstory and establishing her firm place in American history in a way her followers will appreciate and others will admire.

Visit NNPA News Wire Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com and BlackPressUSA.com.