In the year of virtual/hybrid film festivals, the annual Sundance Film Festival adapted its programming to reach viewers around the world in the safety of their homes or at socially-distanced indoor or outdoor venues.

Docs, dramatic films, shorts, series and other variations of video programming screened under the tutelage of new festival director Tabitha Jackson. She’s the first person of African heritage to take on that role and made sure Black talent and an international array of directors, writers, producers and actors flourished under Sundance’s big tent.

BLACK FILMS, FILMMAKERS AND ARTISTS

Ailey (***)

Gifted artists create a spirit so strong that it lives on after they’re gone. That’s the case with legendary choreographer/dancer Alvin Ailey. Documentary director Jamila Wignot records the history, evolution and continuation of Ailey’s work during the renowned Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s 60th anniversary year. Choreographer Rennie Harris is in the midst of creating a dance piece dedicated to Ailey’s style and he puts his mission into context: “A dancer is a physical historian. Valued community information is stored in a dancer’s body.” Former members of AAADT and other admirers reflect and pay tribute to their mentor. Judith Jamison: “Alvin breathed in. We are his breath out. That’s what we’re living on.” Bill T. Jones: “Choreography was his catharsis.” Director Jamila Wignot, with photos, footage, performances and vintage interviews with Ailey, displays a genius’s life that was also brushed with tragedy. A reverent and galvanizing film celebrating dance that’s a reflection of black life created by a pioneer.

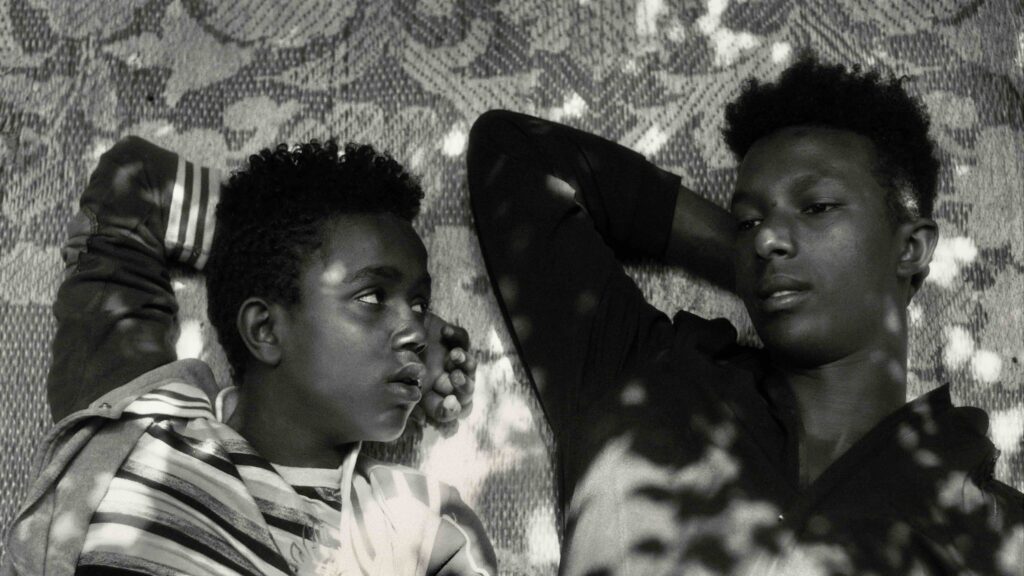

Faya Dayi (***)

We know coffee. We know marijuana. But Ethiopian culture centers around a different drug, khat. It’s a stimulant bound in the leaves of a flowering plant native to the East African country and contains alkaloid cathinone, which causes euphoria, appetite suppression and excitement. Khat chewing is a thousands-of-years-old social custom and the harvesting of the plant is more than a ritualistic tradition, it’s an industry. Filmmaker Jessica Beshir’s contemplative debut documentary captures the lives centered around khat production. Harvesters, sellers buyers. Dads who make their children leave school to help them farm. Offspring who want a better life and consider immigrating to Europe despite the danger: “We shouldn’t have to perish in the desert or seas to enrich our lives.” Shot in stunningly beautiful black and white, the camera lingers on photogenic faces, arched doorways and shadowy figures against windowpanes. Not an ordinary fact-filled doc. The slow pacing is not for the restless. More a feeling, a meditation and a work of art that makes today’s life in Ethiopia look very mid-century.

Homeroom (****)

“F–k it. I’m a senior!” That’s the bravura spirit of the senior class of 2020 at Oakland High School in this profound and revealing documentary by Emmy Award–winning director/cinematographer Peter Nicks. In the beginning, the anticipation of prom and graduation comes across as just a universal rites of passage. Under closer scrutiny, issues surrounding COVID, racism, immigration, gentrification and police presence on campus are affecting academic life. Leading the students through the social, political and educational minefields are student leaders like Denilson Garibo, the Latino son of undocumented immigrants. He’s fearless: “Our kids will open up history books looking at their parents fighting for history.” Equally enlightened is African American student Dewayne Davis: “To make a change in school you have to make a change in environment. Survival comes first. Some kids have no food on the table, no place to sleep.” Sit back adults and get schooled by a younger generation of outspoken activists who just may fix adults’ biggest mistakes. A joy to watch. Dramatic and uplifting.

Judas and the Black Messiah (***)

“Prevent the rise of a black messiah,” dictates J. Edgar Hoover (Martin Sheen), Director of the FBI. So, in the late’60s, local Chicago con-artist hustler William O’Neal (LaKeith Stansfield) is drafted and coerced into joining the Black Panthers. His job is to inform and set up the charismatic Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), the 21-year-old chairman of the Black Panther Party’s Illinois chapter. Screenwriter/director Shaka King (Newlyweeds) along with cinematographer Sean Bobbitt (12 Years a Slave), production designer Sam Lisenco, art director Jeremy Woolsey and composers Craig Harris and Mark Isham set the time, place and mood perfectly—with a film noir effect.

Courage, deceit and rage are displayed in powerful performances by Stansfield, Kaluuya and Dominique Fishback as Hampton’s wife. Wish the camerawork was more kinetic, the intelligent dialogue less dominating and that the storyline focused more on the leader and less on the rat, a scourge on the black community. Still, it’s thoroughly engaging from a historical standpoint. A cautionary tale that should stick with audiences—forever. As Hampton says after a colleague’s death: “You can murder a freedom fighter, but you can’t murder freedom.”

Life in a Day 2020 (***)

Everyday life around the world has keen differences yet many similarities. This crowdsourced documentary, by award-winning director Kevin Macdonald, is proof. It’s been compiled from 324,000 videos from 192 countries and gives poignant glimpses of the struggles and joys of people coping and flourishing in 2020, during a pandemic. A Black doctor sings opera before surgery. Kids go to sleep cradling their smart phones, while a rooster wakes neighbors in another corner of the globe. Home schooling, living in cars, milking goats—the variance in daily routines reminds us that the world turns regardless and its people live on. What’s missing among the scattershot anecdotes are title pages that group clips. Pausing and giving sections specific themes would have anchored and organized the video feeds. That would put them in a greater context, enhance the kaleidoscopic experience and help viewers focus. A heartwarming collage. An illuminating and humanizing reflection of 21st century life.

Ma Belle, My Beauty (***)

Is three really a crowd? Not in this triad love story. A newlywed French/Spanish husband, Fred (Lucien Guignard), has a plan to help his African American wife Bertie (Idella Johnson) get over her depression. He invites her white ex-lover, Lane (Hannah Pepper-Cunningham), to their chateau in the South of France. Be careful what you ask for. New writer/director Marion Hill takes her sweet time laying out the story, rivalries, jealousies and flirtations. Initially, the slow pacing may give you pause. But if you endure, the middle of Act II to the end of Act III has great rewards. The low on the melodrama and high on the personal approach works as you invest feelings in the characters and their buried or frayed emotions. Bertie, Fred and Lane seem so familiar it’s almost like you’re spying on your friends. Johnson and Pepper-Cunningham radiate a sensuality that is captivating and peaks in a well-staged, erotically lit bedroom scene. Bertie: “I’m not gonna lie, I miss having sex with women.” The more “lesbian centric” the film gets, the more enjoyable Ma Belle… becomes. The visually stunning South of France countryside deserves second billing.

Passing (***)

Late 1920s New York. When Irene Redfield (Tessa Thompson, Sylvie’s Love), a light-skinned African American, lowers her hat people can barely figure out she is Black. Her childhood friend Clare Kendry (Ruth Negga Loving), is so light she and her blonde wig have hoodwinked the handsome, rich white racist man John (Alexander Skarsgård) into marriage. One day after rediscovering each other in a restaurant, the two catch up on old times. Claire: “Do you pass?” Irene: “Sometimes.” Later, John, thinking his wife is a tan Caucasian, jokes to Irene: “Claire almost looks like a n—-r.” That’s when Clare’s masquerade repulses Irene and she ditches her. Offended, and hurt, Clare stalks her old friend, insinuating herself into Irene’s family life up in Harlem.

It’s tough to create a story around a dated theme that’s been covered before in classics like Pinky (1951) and Imitation of Life (1959). First-time writer/director Rebecca Hall (actress in Vicky Cristina Barcelona) uses Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel Passing as her step-off. She paints her visions like an artist. Gorgeous B&W cinematography (Eduard Grau), production and set design (Nora Mendis, Kristina Porter), elegant dresses and suits (Marci Rodgers, BlacKkKlansman) and sumptuous music (Devonté Hynes, Queen & Slim) recreate the flapper era. Jealousy breeds contempt adding complications to the narrative. Negga and Thompson play their characters so well it’s as if they just stepped out of the Turner Classics Movies channel. Their voices, banter, mannerisms and style of walking is so ’20s you’d expect Zora Neale Hurston and Josephine Baker to walk around the corner. André Holland as Irene’s doctor husband is debonair. The premise is so repugnant, audiences may flinch at the prospect of watching a social/racial malady that should have never existed. If they do, they will miss an impeccable recreation of the Harlem Renaissance era—warts and all.

Summer of Soul (… Or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (****)

It was a volatile time. Malcom and Martin had been assassinated in recent years. Civil uprisings and riots had just simmered down. The summer of ’69 was a chance for a cultural break. That happened in Harlem’s Mt. Morris Park, when program director Tony Lawrence created the summer long Harlem Cultural Festival. Three-hundred thousand music lovers. Few to no cops in sight. The Black Panthers provided security. It’s a mellow celebration. Tonight Show musical director Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson flicked the moth balls off the footage shot by producer/director Hal Tulchin for an unreleased 1969 doc called Black Woodstock. It had languished in a basement for 50 years. Among the many stellar performances: R&B artists (BB King, Little Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone); jazz greats (Abby Lincoln, Nina Simone, Mongo Santamaria) and gospel singers (The Staple Singers, The Edwin Hawkins Singers, Mahalia Jackson). Mayor John V. Lindsay makes a cameo and activists like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton share their opinions on music and the state of Black life. Sharpton: “Gospel was more than religion. Gospel was the therapy for the stress and pressure of being Black in America.”

Vintage performances are edited in with news footage and current interviews from fest musicians recollecting their performances. Their perspectives add footnotes to the social/political history surrounding these unforgettable outdoor concerts. Before there was Prince there was Sly. We know this because Questlove and his rousing, thoughtful documentary links us back to the past with this precious and rare archive.

For more information about the annual Sundance Film Festival go to: https://www.sundance.org/festivals/sundance-film-festival/about.

Visit NNPA News Wire Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com and BlackPressUSA.com.