(**1/2)

“Disco is like the mom who gave birth to a couple of babies: Hip Hop and House Music.” If that’s the case, mom’s second child is getting its own bio.

House music has been around since the 1970s, and most claim it originated in Chicago. In fact, an underground dance club called “Warehouse” is where the genre got its name. With some of the OGs of the form still alive to tell their stories, director Elegance Bratton (The Inspection) does some sleuthing. He traces the vibe from its inception through its commercialization, transformation into electronic dance music and its resurgence. With Bratton at the helm, the roots of a music developed by gay Black DJs gets tracked back to its genesis.

DJ turned record producer Vince Lawrence is one of the pioneers of the sound. Growing up on the South Side of Chicago, he was inspired by civil rights icon Jesse Jackson and his “I am somebody” philosophy. That fueled Lawrence, who was inspired to find his own path, which led in and out of the gay and Black communities.

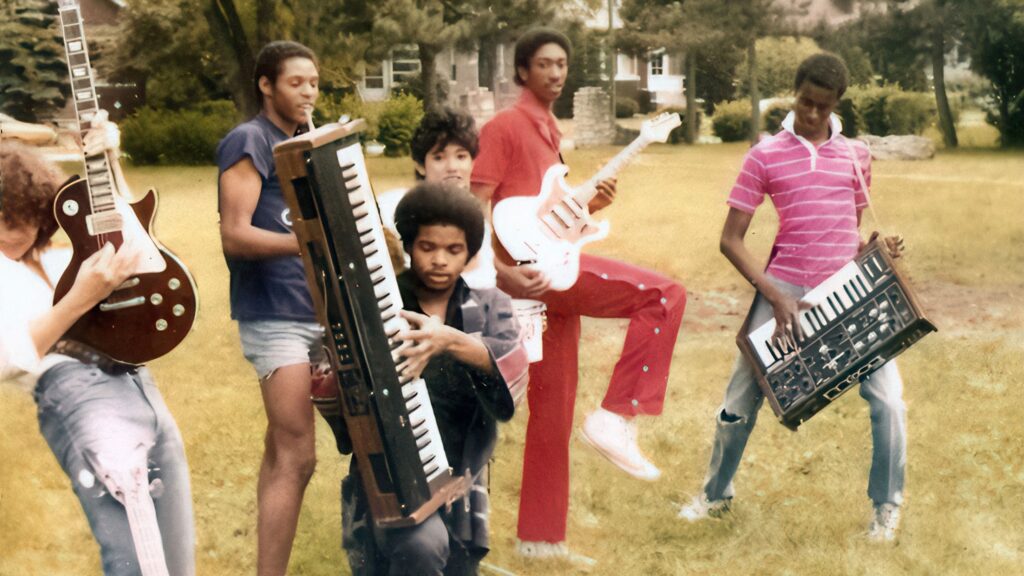

Raised in a low-income but loving family, one year when Lawrence was 14 years old, summer camp was too expensive for his family. Instead, he was offered a summer gig as a roadie for Eddie Thomas, a record promoter most known for managing The Impressions and Curtis Mayfield. It changed the teenager forever: “I’m this nerdy kid and I’m trying to find my way. Then I saw a synthesizer!!!”

And so, Lawerence’s introduction into music, by seasoned professionals, ignited something in him. A sense of creativity and beats developed as he cultivated a music style that delighted dancers in clubs. A synthesizer was his collaborator and savior. “Make any sound from an instrument, with buttons? I’m going to make the music of the future.” And he did. When the film focusses on interviews, archival footage, photos and Lawrence’s wild exploits, it’s as exciting as the music itself. It pulsates. Especially when it also showcases OGs like Frankie Knuckles and Larry Lavan. Legends of the genre.

When the doc narrative turns to the commercialization of the form and takes the viewer/listener down a path where Lawerence loses momentum and success due to the ills of the record industry, a dark cloud perches over the footage. Bitterness towards the white singer Rachel Cain, a former punk rocker who did lead vocals on a breakout hit for Lawrence, could have been deleted from the final cut. Grievances against a manager who was funny with the money, a cliché in the industry but necessary cautionary tale, sound sour. Sure, the central figure should speak his truths. Certainly, it isn’t fair that he didn’t make a fortune from a successful art form he helped invent. That should all be aired. But it puts a damper on this documentary. A blight that never goes away.

Bratton’s strategy of pulling in the historical events of the time is a blessing and a curse. It puts Lawrence’s experience into perspective and highlights that oppressed communities who sought refuge in clubs with like-minded people. Also, the segregation in Chicago under Mayor Daley was notorious. History is important, but not more than the music. A times the regurgitaton of old news seems like a crutch. Most folks yearning to see a doc like this are coming to enjoy the sounds, melodies, rhythms, musicians and singers associated with house music. That should have been the film’s aim.

Director of photography Lisa Rinzler finds the right angles and lighting. Editors Kristan William Sprague and Jeremy Stulberg know when to nip and tuck. Composer James Newberry adds his own score to the audio track, when it fits. While the production design is adequately done by Tommy Love.

Lawrence is a center of attention and worthy of the spotlight. However, no one is going to the theater or tuning in to watch someone sing the blues when joyous house music should reign. Why is this well-intentioned doc so depressing? It shouldn’t be. It should be a celebration.

No one is going to the theater or tuning in to watch someone sing the blues when joyous house music should reign. Why is this doc so depressing? It shouldn’t be. It should be a celebration.

Photos courtesy of the Sundance Film Institute. Photo by Vince Lawrence

For more information about the Sundance Film Festival go to: https://festival.sundance.org

Visit Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com.