Feature films and documentaries entertained and enlightened audiences at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. The non-fiction films were as compelling as the crime thrillers, family dramas and adolescent romances. Nearly all left a lasting impression.

Cha Cha Real Smooth (***1/2)

Twenty-three-year-old writer/actor/director Cooper Raiff knows how to capture the attention of rom/com audiences. Andrew’s (Raiff) life is adrift in the New Jersey ‘burbs. Just out of college and working for peanuts at a fast-food restaurant. He’s back home living with his mom (Leslie Mann), stepdad (Brad Garrett) and little brother (Evan Assante). He finds his calling one day after attending a bat mitzvah, where he revved up the guests and a parent recommended that he do it professionally. When he becomes a party-starter, something like a cruise ship social director, the aimless young man finds purpose and a chance meeting with a kid’s mom Domino (Dakota Johnson) sets his heart aflutter. But can the often-inebriated Andrew keep his act together? Like “Dude where’s your next bat mitzvah? Do you even know?”

As a writer Raiff has created a refreshing premise and an endearing glimpse into Jewish culture. Expect to be charmed beyond words by the jovial twentysomething who needs a break and the May-December romance. As a director, he has a strong feel for pacing (editor Henry Hayes), pulls vibrant performances from his cast and sustains an amiable tone for 107 minutes. As an actor, Raiff steals scenes. He’s vulnerable, funny, quirky and would make a perfect lead in a sitcom, streaming series or adventure movie. Finally, Johnson’s often airy, spacey approach to acting makes perfect sense in her role as the ambivalent mom. The supporting cast is equally up to the challenge: Raul Castillo as Domino’s jealous fiancé, Vanessa Burghardt as her daughter and Colton Osorio as David’s friend. Perfectly shot (Cristina Dunlap) with a very sweet singer/songwriter musical score (Este Haim, Christopher Stracey) and plenty of funk music at the parties. This sweet romantic comedy will make you smile long after it’s over.

Emily the Criminal (***1/2)

The crime thriller genre is so routine, what could make it less formulaic? How about a taut script and smart direction by John Patton Ford and a gutsy performance by Aubrey Plaza (Parks and Recreation). Former art student Emily (Plaza) is a Gen Zer drowning in college loans, hampered by a blemish on her criminal record and weighed down by minimum wage jobs. When a $200 per hour gig comes her way, she jumps on it. What’s the rub? She’s trained by two crooked brothers, Youcef (Theo Rossi, Sons of Anarchy) and Khalil (Jonathan Avigdori), to buy TVs at department stores with bogus credit cards that are resold. Hey, it’s a living and she looks the part. Her nondescript face and lowkey demeanor fool store clerks and salesmen and serve her well as she enters a life of crime and becomes a embittered woman: “Mo—-f—k–rs will keep taking from you and taking from you until you make the goddamn rules yourself.”

The increasingly innovative story and unlikely protagonist keep you guessing and wanting to see if Emily can con her way forward. The backstreet L.A. setting is so simple and the characters so ordinary nothing seems out of the realm of possibility. Ford’s direction milks the actors’ dissention, piques the violence at the right times and plays with the film noir tone just enough. For a first-time filmmaker, he shows enough talent to warrant big-budget movies or series. Plaza’s perceptive acting makes Emily so wronged you want to see her beat the system and the bad guys. Rossi has the right mix of criminality and softness. Clothes fit the characters. Cinematography is invisible. Editing just about right. Ford turns a person gone astray into a hardened criminal in 93 increasingly cynical minutes. It’s a feat the Safdie brothers accomplished with Uncut Gems. And Plaza is as convincing here as Adam Sandler was there. Rarely do low-budget crime thrillers get as shamelessly gritty as this.

La Guerra Civil (***)

On the surface, TV actor turned doc director Eva Longoria Bastón has pulled together the definitive accounting of an iconic 1996 boxing match. A fight between East L.A.’s Mexican-American fighter Oscar De La Hoya and Mexican pugilist legend Julio César Chávez. Says Oscar, “Holy s–t, I’m fighting my hero. What the F–k!” It’s the glamour guy against the blue-collar battler. Young vs. old. Their rivalry divides fans’ allegiances causing friction, speculations and betting quandaries. Says one devotee: My heart is with him (Chavez), but my money is with Oscar.”

Under the surface, Longoria Bastón explores and champions two different cultures—Mexican and Mexican American—that might seem homogenous to the outside world but have real distinctions in the Chicano community. Lots and lots of history, bio info, trash-talking and swag steps into center ring along with the backstories of two disparate sports heroes. Their anecdotes, families, friends and sports journalists share experiences that are precious and need to be preserved. The director’s filmmaking approach is as traditional as it is skilled. The real verve comes from the auras and conviviality of the two charismatic boxers. Hoya’s commentary on the fight is blunt and sincere. Chavez, as the aging hero who won’t admit defeat, is like a lion king realizing his power is fading. Mario Lopez and George Lopez’s anecdotes add energy. Two men, who defined and redefined boxing, are hailed by their Latino communities and everyone is invited to their homage.

Living (***)

Post WWII, Mr. Williams (Bill Nighy) is a stodgy, older London civil servant exec who’s set in his ways. So are most of the employees in his nearly all-male Public Service office. He isn’t ruffled when a project to turn a vacant lot into a playground for needy kids is presented to him. He simply sends it on to another office. Paper pushers push papers. Nothing more. And the reports and applications on his desk are piled as high as a skyscraper. Only after being diagnosed with a terminal illness does the conventional bureaucrat venture from his routine. His aim: “Live a little. But I don’t know how.” Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece Ikiru (To Live) is the source material. Author Kazuo Ishiguro wrote the script and director Oliver Hermanus (Beauty) puts their visions into motion.

Banal 9-5 dialogue suits the emotionless office clones and sets up a yearning for drama. Once the bad prognosis enters, it’s easy to feel sorry for the stiff protagonist. In fact, his end-of-life journey becomes a state of grace that is quite touching. Hermanus aptly establishes a stuffy, predictable decorum, masterfully depicting the archetypal hierarchies, ass-kissing and group dynamics in places of business. Cinematographer Jamie Ramsay (Mothering Sunday) has an exceptional eye for composition. The color palette by art director Adam Marshall is so 1950s it firmly sets the time and place. Ditto the costumes and production design. Big band string music helps too. Together, all the evocative production elements make this small personal drama extremely atmospheric. Nighy’s performance is so minimalist his few displays of deep emotion are monumental. Aimee Lou Wood as the one employee Williams befriends has a breezy spirit. Taking a tiny slice of life and letting it segue into a life-affirming metamorphosis takes real skill.

Lucy and Desi (***1/2)

Comic actor turned director Amy Poehler didn’t have to reinvent the doc genre to make a very absorbing bio non-fiction film. All she needed were Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, arguably the most iconic TV pop stars ever. Their personal story, that of an interracial couple battling the white Hollywood establishment, is so riveting it feels like it happened yesterday and not 71 years ago. Aaron Sorkin’s Being the Ricardos took a glimpse at their lives. Poehler’s exhaustive family album delves into backgrounds, first dates, marriage, infidelities, working relationships and their pioneering efforts that ushered in the TV sitcom era.

From the photos, footage and what we learn about Desi’s roots, this may be the first time folks realize he was a man of color with a keen attachment to Afro-Latino culture, best exemplified by the music he sang and the congas he played. Also, the couple’s steadfast efforts to transcend prejudice is duly noted. The overwhelming amount of their own audio tapes makes this doc intimate and personal. It’s like you’re following them through time—birth to death. Forward and backward. Poehler assembles all the moving parts like she’s fitting a life puzzle together. Admirers like daughter Luci Arnaz, Bette Midler, Carol Burnett and Norman Lear testify to their genius. However, Lucy and Desi are the stars. The sun and moon too.

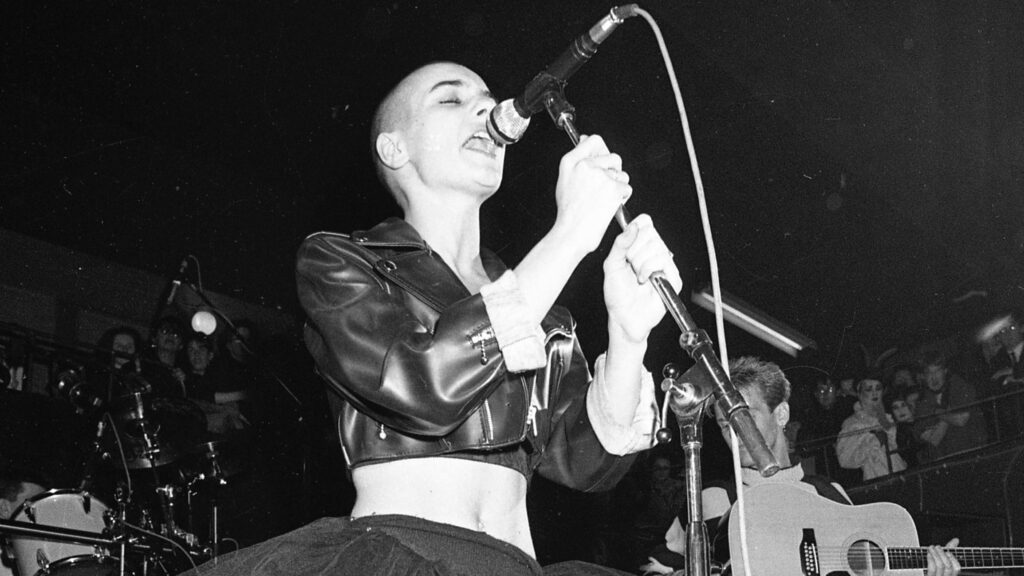

Nothing Compares (**1/2)

Not everyone knows why she did what she did. To clear that up, Sinéad O’Connor candidly recalls her childhood (abused by her mother), her time in a girls’ home (the Magdalene laundries abused women and she exposed it) and dealings with the record industry (they made her change the cover of her first album). All of it is enough to make an artist rage: “I got into music because of therapy. I just wanted to scream.” As she reflects on the good and tough times and progressive opinions on abortion, women’s rights and contraception, viewers will realize she was ahead of her time and clearing a path for other assertive female musicians who would follow. Would there be an Alanis Morrisette without a Sinéad?

Director/writer Kathryn Ferguson captures O’Connor’s essence, records her story and gives her props via interviews and archival footage. She also tackles moments that labeled the singer as enigmatic (rips photo of Pope John Paul II on SNL). This documentary is comprehensive and meditative, but it doesn’t spend enough time on her mesmerizing voice and earthy performances. Note that Prince’s estate would not let Ferguson use Nothing Compares to You, the singer’s signature song. But she had other hits, other music that expressed her thoughts and well showcased her haunting soprano voice. Some fans would pay good money to hear her scream out “Fire in Babylon” or sensitively sing “Black Boys on Mopeds.” Showing the turndown emails from Prince’s heirs would have cemented the case that she is still in a struggle. At the film’s end, there she is on stage, a middle-aged woman chanting her hit “Thank You for Hearing Me.” That’s when you realized her biggest gift, her voice, gave her a vehicle to expose injustice—hers and others.

Resurrection (**)

Something about Rebecca Hall’s demeanor, voice and persona makes her appear very accessible. Almost like you know her. But you don’t. It’s a gift. You have it or you don’t. It worked well in The Town. That’s how she pulls you into this aimless drama that deteriorates into an inane psychological thriller. Albany, NY single mom Margaret (Hall), fusses with her teenage daughter Abbie (Grace Kaufman) and is a pharma company exec. Life is routine until she spies a mystery man at a conference. It’s David (Tim Roth), an ex. She knew him as a teenager, he was her much older lover. A sadist who commanded her do strange things. She becomes ultra-nervous as he pops up in stores and on street corners. Panicked, she alerts the police. They do nothing. She’s on her own.

Writer/director Andrew Semans should apologize to Hall for hiring her to be a decent character turned nutjob harassed by another nutjob. The S&M relationship that ensues may make viewers hurl and question what power a tiny little man could have over a grown woman? A power that convinces her to walk to work barefoot or sleep overnight in a park just cause he says so? There are repulsive and pointless head games that no amount of revenge can justify. The film’s miniscule horror elements don’t compensate ether. Roth is creepy, but so diminutive a strong wind could blow him over. Michael Esper as Margaret’s booty call man is better cast. The entire production team creates nice-looking footage but is wasting its talents. Hall will leave this loser film reputation intact. Semans, maybe not. Ditto Hall’s agent for not saying: “No. Don’t do it.”

The Janes (***)

They’re unsung heroes. Activists of the 1970s shaped by the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements and testing new ground. They provided a safe place for women to have abortions way before they were legalized. Out of that need, The Jane Collective was born. Smart women in the Chicago area taking charge. They operated clandestinely but people knew. How? Years later, as senior citizens, the women look back and a member named Katie sums it up: “Men’s underestimating women came in handy—they were oblivious.” It was also known that male judges, police officers and lawyers needed their services for their lovers and girlfriends too and turned a blind eye.

Documentarians Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes interview the old crusaders who were brave beyond society’s conception back then: “You had to be married to get a diaphragm or birth control pills.” That’s how bad it was. Though most of the members were white, concerns about privileged backgrounds and racism were on their minds—especially as their clinic was accessed by women who did and didn’t look like them. Marie Leaner was a Black member who recalls those conversations. She also helped the group find a lawyer when some got arrested.

The collective’s self-empowerment reached new heights when they learned to perform safe abortions themselves. Newspaper headlines, old footage of political/social marches and clips of the younger women back in the day fill in the details of these strong-willed advocates. Says one, “I was afraid all the time, but I was a warrior for justice.” That sentiment has been duly recorded in doc that should be a cautionary tale for today’s apathetic generation.

When You Finish Saving the World (***)

Family drama takes a turn left in this biting satire. That’s the way actor/director Jesse Eisenberg planned it. Somewhere in a nondescript Indiana ‘burb bedroom, teenager and budding singer/songwriter Ziggy (Finn Wolfhard, Stranger Things) broadcasts his milk-toast music to his podcast audience. When his mom Evelyn (Julianne Moore) interrupts, he goes ballistic. That’s how their loving and antagonistic relationship works. They press each other’s buttons. He is oblivious to anything socially relevant. She runs a women’s crisis center. They clash and makeup. Clash and makeup.

In Eisenberg’s satiric world, being woke is never enough and those who think they’re savvy are not without faults. That’s best depicted when the hypocritical mom chides her low-conscious son: “You haven’t done the work. If you don’t make an attempt to understand the issues that are affecting society, then your issues extend far beyond impressing your classmates.” Then the self-righteous mom shamelessly flirts with a financially challenged high school student. The divergent people, personalities and paths are well set in the first 10 minutes. Each character’s dialogue well represents them, and the annoying, loving mom/son bickering is routine all over America. Moore establishes the humorless Evelyn well. Wolfhard is suitably self-absorbed, and Alisha Boe (TV’s 13 Reasons Why) makes a beguiling Bohemian-type student. Pity the footage loses pace, momentum and purpose around the hour mark. A very Sundance indie style of filmmaking. The kind that seems to make Eisenberg smirk with joy.

For more information about the annual Sundance Film Festival go to: https://www.sundance.org/festivals/sundance-film-festival/about.

Visit NNPA News Wire Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com and BlackPressUSA.com.