The lineup at the 2020 New York Film Festival included an impressive array of African diaspora films and the festival’s usual collection of international motion pictures.

Attesting to NYFF’s eagerness to hear black voices, the fest featured three main slate films from British director/writer Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave) that are part of a five-episode West Indian community-based mini-series Small Axe. McQueen’s homage to his Caribbean roots will appear on Prime Video later this year. Other NYFF entries will roll out in theaters, VOD and on streaming services—in months to come.

All In: The Fight for Democracy (***) If voter suppression doesn’t spark righteous indignation, nothing will. To understand the gravity of the problem, reflect on the findings of directors Liz Garbus and Lisa Cortés and 2018 Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. The history of voting machinations goes back to the 1700s, when only white people who owned land could vote. Eventually others could, but progress was followed by regression: poll taxes, literacy tests and a 2013 Supreme Court ruling that gutted parts of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Abrams walks you through the devious ways people are denied their rights to elect politicians and specifically points to the artifices used to stifle Georgia citizens’ rights and impede her ability to become governor. The facts and figures the doc have amassed are so alarming that they will make you treasure your right to vote. Timely. Illuminating. Required viewing. The weaponization of voter suppression is unmasked by very astute filmmakers and an exceedingly brave politician.

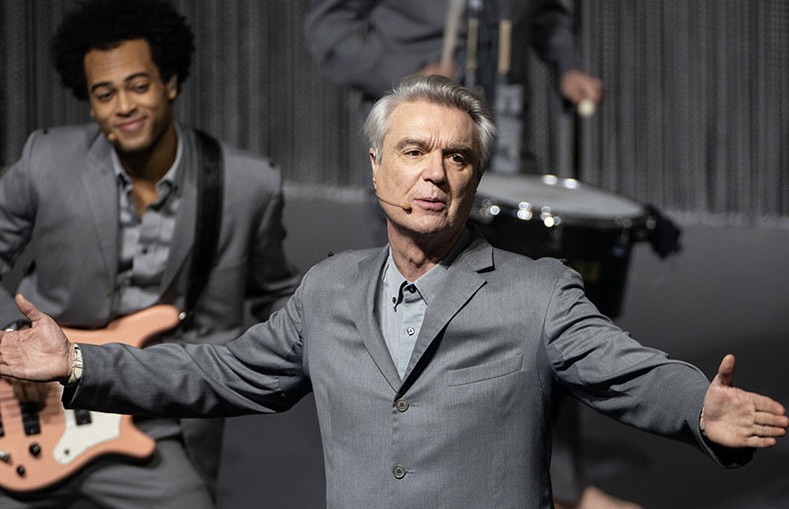

David Byrne’s American Utopia (***) A good shot of ‘80s rock music—you gotta love it. Talking Heads legend David Byrne’s Broadway musical has been recorded on film by director Spike Lee. And now, Lee seems much more willing to test the boundaries of creatively filming a live theater piece than he was with Passing Strange in 2009. Viewpoints (cinematographer Ellen Kuras) from the front, top, back and the sides of the stage pull you into the piece. An energized and crowded theater generates a euphoric atmosphere, while natty gray costumes and glistening beaded curtains add a contemporary feel.

The very philosophical and intellectual Byrne and his spirited team of singer/dancer/instrumentalists (Jacqueline Acevedo, Gustavo Di Dalva, Daniel Freedman, Chris Giarmo) raise the roof. “Burning Down the House” and “Slippery People” are among the timeless songs. At 68-years-old, Byrne’s voice is not as pliant as it used to be, but still strong. Protest songs and homages to the BLM movement resonate. Deleting one or two numbers off the playlist and ending the doc in a more decisive manner would have helped the pacing (editor Adam Gough). A high-spirited charmer. Will make your soul jump as it reflects the past and mirrors the times we live in with equal verve.

The Disciple (***) Traditional vocal Hindustani music from Northern India dates back to the 12th century and weaves improvised tones into a spontaneous mosaic of sounds. Indian filmmaker Chaitanya Tamhane displays a certain reverence for the art form’s past and its transitions into the 21st century. Kayal, one the most important Hindustani genres, is adored by Sharad (Aditya Modak), a disciple who follows in his father’s footsteps as singer. His quest to keep the music alive and unblemished takes viewers on an excursion around India as elements of the old country clash with a new more commercialized era.

The singing with its dulcet tones has a mystical, spiritual effect. The strongest scene features Sharad throwing a drink in the face of a disrespectful journalist. New actor Modak carries the weight of the film on his shoulders quite nicely. Well shot, produced, written and directed. Chaitanya Tamhane sends a transcendental postcard from India filled with soothing music and enlightening insights as the old mixes with the new.

I Carry You with Me (***1/2) In Mexico, Iván (Armando Espitia), a closeted father/restaurant worker is having an affair with Gerardo (Christian Vazquez), a single and out gay teacher. This initial premise seems as dated as it is cliché. But, as the film progresses, you’re drawn into the dishwasher’s ambition to leave Mexico and head to the U.S. for a better life. It’s a vitalizing plot turn. Further in, the story and its actors melt into real life, as the actual, older Iván’s life blurs the lines between feature film and documentary.

It’s innovative, amazing and hybrid filmmaking by first-time director Heidi Ewing. She co-writes with Alan Page an impressive, inspiring and quintessential “American Dream” story—the kind that counteracts the current negative images of immigrants. Culture clash, social status conflict, enduring friendships and the U.S. as a safe harbor are on view. Gerardo: “They hate us over there.” Iván: “Then why does everyone who leaves stay there?” Poignant dialogue, three-dimensional characters, superb acting by all and a story that needs to be told over and over again.

Lovers Rock (****) “I should have worn my church shoes,” says Martha (Amarah-Jae St. Aubyn). “You can’t wear church shoes to a blues party,” replies Patti (Shaniqua Okwok), her friend. The two young women head to a West Indian house party in this very evocative and visually stunning period film by writer/director Steve McQueen (12 Years A Slave). The festivities take place in 1980s London, where the magic of dance and reggae/pop music put a joyful aura in the air that’s so powerful party goers sing along to the music like they’re in a Broadway show. The thinly plotted drama/romance follows Martha as she meets the very debonair Franklyn (Micheal Ward).

It’s all about the mood, music, images and feeling as McQueen recreates a time when Caribbean expatriates held on to their culture by socializing. McQueen takes his time painting this indelible portrait. Shapes, colors, textures, sounds, clothes and setting define the movie. A work of art. A complete surprise. Gorgeous (cinematographer Shabier Kirchner). Hard to wrap your head around this much artistry. But you must. As the DJ says, “Move your feet. You don’t know who’ll you meet.”

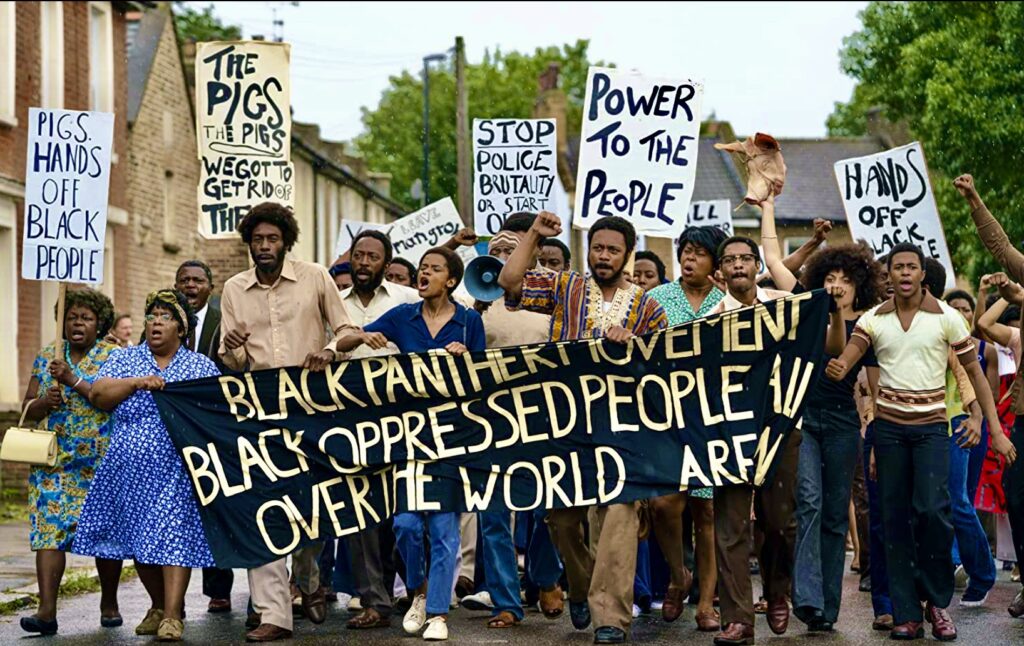

Mangrove (***1/2) In the Nottinghill section of London in 1968, the West Indian community has taken the neighborhood restaurant Mangrove into its heart. The café is run by Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes, TV’s Lost in Space), a Trinidadian immigrant who is as proud to serve émigrés and local activists curry goat as he is to offer them a community center. Police harassment is part of daily life. Says Darcus (Malachi Kirby, Roots), a Black Panther: “The police will have to stop it or the Black community will have to stop them.” It’s a sentiment echoed by his comrade Altheia Jones-LaCointe (Letitia Wright, Black Panther). Continued brutality incites a neighborhood march, which involves a clash with the cops. Nine people are arrested, imprisoned and dubbed the “Mangrove Nine” as they fight for their freedom in an impassioned court case.

The story, written by Steve McQueen and Alastair Siddons and directed by McQueen, is based on fact and displays waves of police violence so disturbing it will hook audiences into the plight of those on trial. When the restaurant crew goes berserk in a cop station after one of theirs has been beaten, the movie hits a level of blistering drama that is sustained throughout the rest of the film. Oscar-caliber performance from Kirby, Wright and Parkes. With an evil judge, conniving prosecutors and lying police vs. courageous activists, McQueen shows a gift for courtroom drama on the level of Sidney Lumet’s (12 Angry Men). Steel band music and Toots and the Maytals singing the classic reggae song “Pressure Drop” help this reverent feel for West Indian culture and an unwavering quest for justice resonate.

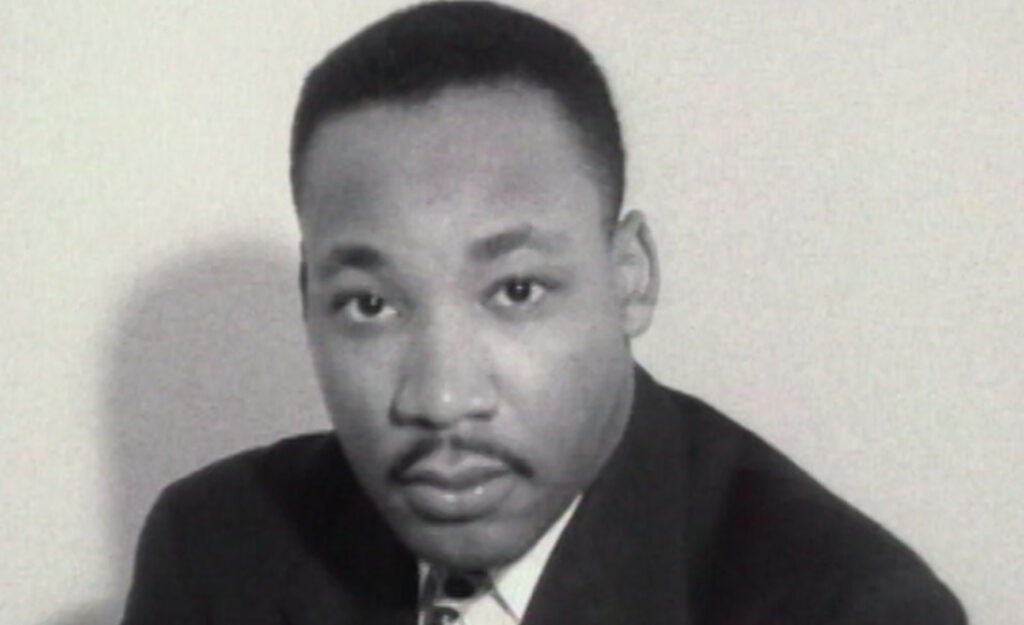

MLK/FBI (***) J. Edgar Hoover’s evil attempts to silence Martin Luther King in the ‘60s are notorious. But it took documentarian/director Sam Pollard (Mr. Soul!) and co-writers Benjamin Hedin and Laura Tomaselli to draw a straight line between the FBI and King based on newly declassified files. Hoover feared the rise of a Black Messiah, and his racism and paranoia motivated him to connive. Tapes from hotel rooms, files and archival footage are all assembled meticulously and presented like a professor teaching a grad course or a prosecuting attorney building an airtight case.

Clips of RFK, JFK, Andrew Young and informants abound. Images of MLK railing against segregation and the War in Vietnam are iconic: “No money for the war on poverty. But money for (Vietnam) war.” Be prepared to be deluged with pertinent facts, data so detailed and academic general audiences may feel overwhelmed. Which would be a shame. Films that divulge the reckless behavior of the FBI and/or government should be seen so the country doesn’t repeat that kind of malfeasance that leads to civil rights leaders being maligned and murdered.

Nomadland (***) Itinerant Americans, sometimes of an older age and living off low-wage jobs, are particularly susceptible to a down economy. That was depicted in Jessica Bruder’s 2017 nonfiction book Nomadland. Now a face is attached to this demographic, as created by writer/director Chloé Zhao’s (The Rider). Her poignant script looks at the nomadic existence of transient people who live within the margins of the low-cost labor pool. Fern (Francis McDormand) resides in her white van, using it to travel to seasonal jobs. She’s a rolling stone, dismissing lovers (David Strathairn) and keeping family members at bay. Says her sister: “It’s always what’s out there is more interesting.”

Fern’s work ethic and ability to fend for herself grabs your attention. She’s eccentric, and always finding new means to fit into each town: “Great way to know a place is to go to AA meetings.” As a commentator, Zhao observes and never judges. McDormand plays another “everywoman” with a strength and vulnerability that is always compelling. Faint, simple piano music caresses the score (Ludovico Einaudi). Perceptive cinematography (Joshua James Richards, God’s Own Country) makes America’s West inviting. This is how the other half lives. The half that is most often neglected and growing in numbers.

On the Rocks (**1/2) Felix (Bill Murray, Lost in Translation) is the father of an adult daughter (Rashida Jones) who is having marital problems with her very successful husband (Marlon Wayons). Dad sticks his nose in their business and nothing goes right. Why would it? Writer/director Sofia Coppola seems to have fun spinning this eccentric romantic dramedy. When the film focuses on modern family life (Felix and his biracial grand kids playing cards) it’s on target. Its attempts at humor are not as consistent. The exception is a sequence when dad and daughter track her man’s whereabouts to Mexico, which becomes a comedy of errors.

Sometimes the film feels too affectated, sometimes it seems like Coppola is on top of her game. Nice understated performance from Jones. Wayans is miscast in a role that a veteran romantic actor would nail. As for Murray? His Felix may be an acquired taste. His fans will laugh every time he smirks. Others may not. The daughter sums it up as she confronts her dad: “It’s exhausting trying love you enough.”

Red, White and Blue (***1/2) “Your talent doesn’t belong behind closed doors. You should be a benefit to the community,” says a mentor. Those words steer Leroy Logan (John Boyega, Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens), a young forensic scientist, towards recruitment for a local police force in his West Indian neighborhood in 1980s London. Watching his father Ken (Steve Toussaint) get physically abused by the cops is another driving force. Leroy ‘s good intentions for reform meet with resistance from fellow cadets, and subsequently fellow constables in the Metropolitan Police Force and his commanding officer.

Filmmaker Steve McQueen with co-writer Courttia Newland (Lovers Rock) expertly recreates a true crime/drama story that captures the depth of police rancor and an officer who dared to fix it. Boyega’s stirring performance reaches extremely high levels of drama and indignation, the kind few of his other roles offered. He deserves an Oscar nom. Tense scenes between the do-right son and wronged father ache with sadness, fear, betrayal, stubbornness, discord—then healing. Toussaint and the supporting cast—from the family to the police characters—are electric. Watching West Indians and Pakistanis be abused makes you see the urgent need for a transformation. A searing exposé. Excellent. Fiery. Courageous filmmaking that demands an end to inhumane policing and systematic racism.

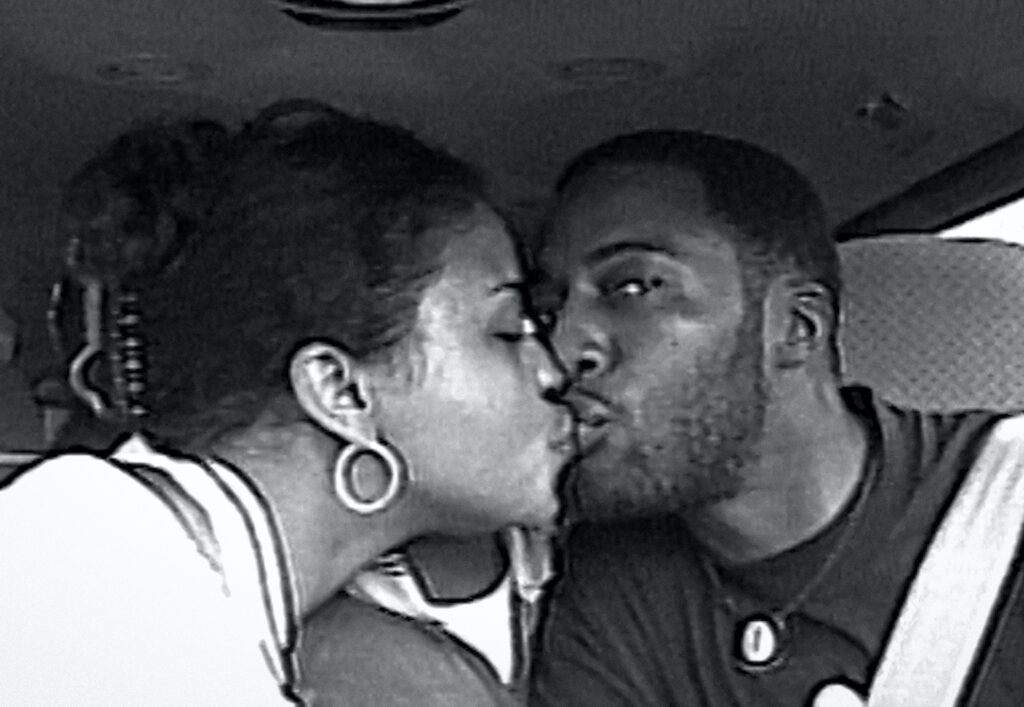

Time (***) There’s a certain, tangible power in redemption. That’s what’s on view in this thoughtful and inspiring documentary about a Louisiana couple trying to pull their life back together. Twenty years ago, Fox Rich and her husband Robert opened a hip-hop store with bright plans for their future. Bad breaks and setbacks left them penniless and desperate, to the point where they orchestrated an armed bank robbery, which went awry. Crime of poverty? Just a very stupid choice? Fox’s mother sums it up: ‘Right don’t come to you when you’re doing wrong.” Both spouses were sentenced to prison. She got out first, trying every day to rebuild her life and raise her kids to be good citizens.

Documentarian Garrett Bradley puts all the pieces together so viewers can see the after-effects of breaking laws, the callousness of over-lengthy sentencing and a propensity to punish and not rehabilitate. Fox’s steely determination to use her predicament as a learning tool and make amends is commendable and surprisingly uplifting. She exhibits a force of goodwill and positivity that seems genuine and endless. Photos, archival footage and new interviews equate prison with slavery and redemption as the best check against reincarceration. Sparse piano music augmented by strings shows up at the right times. This documentary dares to be humanizing and forgiving at a time when dehumanization is so mainstream.

For more information about the New York Film Festival go to: https://www.filmlinc.org/daily/category/nyff/

Visit NNPA News Wire Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com and BlackPressUSA.com.