(**1/2)

If you’re Black and you attended a predominately white college or high school, all this sounds familiar.

There was likely a Black table in the lunch room where you gathered. Not due to segregation. More as an oasis in the middle of an ocean of people who didn’t look like you. In that way this doc has a universal theme. In other ways, it feels like a class reunion with anecdotes.

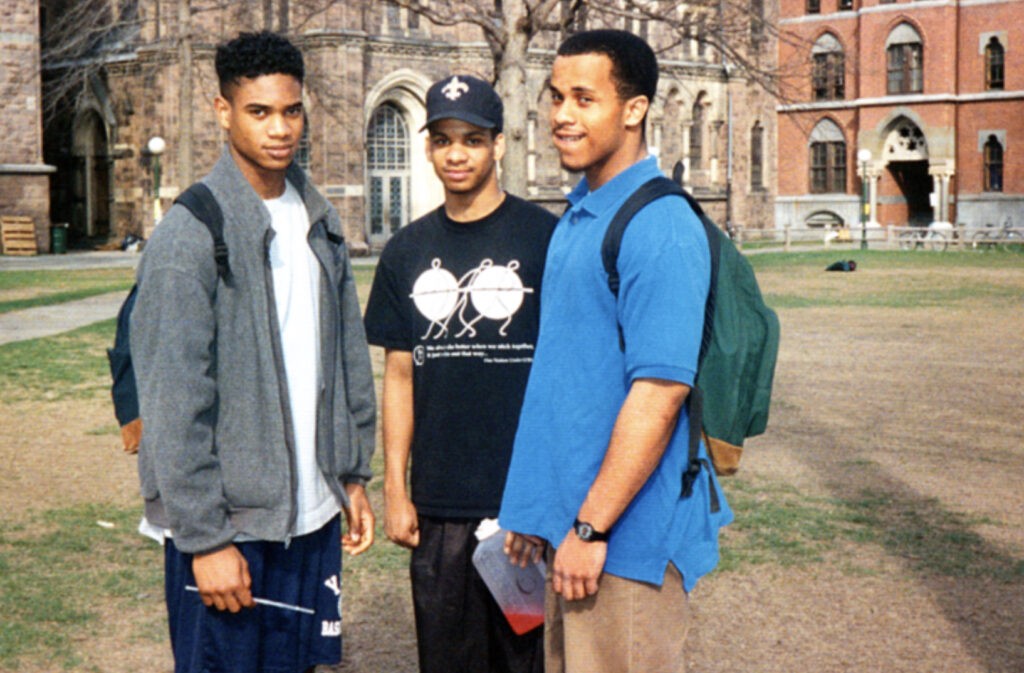

DDocumentarians John Antonio James and Billy Mack helm this recollection of breakthroughs, incidents, tribulations and graduations that plays out like you’re looking through a narrated photo album. One that takes you back to the 1990s and an Ivy League university that dates way back to 1701. For the alumni, they can vividly recall the sense of prestige they felt for entering, living through and moving on from Yale College. But at what price? Was the trauma inflicted on these Black students worth the effort? What comes next doesn’t consistently support that.

Personal experiences, slights, prejudice and degrading events are duly noted and recorded. Also, a need to build a bond to survive is substantiated. Specifically, these former students would pull a bunch of tables together in the gigantic Commons Dining Hall, and that act of comradery and defiance brought them refuge and a sense of identity.

Any person of color who attended a university, where Blacks and other POC were a distinct minority, understands this basic need. Especially before during and after the height of Affirmative Action policies, when some in the dominant culture assumed minority undergrads were only on campus because of a favoritism. Of course, that misguided opinion doesn’t make sense as students still have to have exceptional grades and SAT scores to enter.

Also, donor and legacy admissions far outnumber any boost POC’s got. According to Yale Daily News: Rates of admission are nearly seven times higher for donor-related applicants than for non-donor-related applicants and nearly six times higher for legacies than for non-legacies.

One of the more egregious incidents the undergrads faced was the arrest of Black students for a conflict at a late-night campus restaurant where the police took the side of a white restaurant clerk and not the African American kids. That’s something worth noting. Yet somehow, in spite of challenges like that, they graduated in 1997, as one of the largest groups of Black students ever to pick up their degrees at Connecticut’s most famous university.

Sometimes the intentions of the doc and its possible reception are an iffy mix. Some audience members may think, if you went to Yale, a predominately white school, what else were you expecting? If you managed to graduate and go on to a successful career, is that really noteworthy enough to warrant a documentary film? Plenty of Black students around the country had the same experiences. Nothing viewed here for 93 minutes seems that different from what others have faced. E.g., one very insulting incident feels like it might have played out on many campuses: a Black incoming student meets his new white roommate and the roommate’s dad wouldn’t shake the hand of the Black student’s father. Unfortunately, that’s quite fathomable. Certainly this groups’ experiences are valid, enlightening and have teachable moments. But not in an extraordinary way.

Several missed opportunities might have brought this doc up a level: How did these kids interact with other students from different cultures, nationalities and ethnic backgrounds? If the mixing of ideas is one of the purposes of higher learning, none is on view here. What if Black and white alumni had discussed how they felt about the ups and downs of culture clashes, affirmative action and integration—from both sides of the fence? Challenging debates like that would have been provocative. Dissention is a good educational tool—use it. Or what if Black alumni from Yale and from HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) had shared the differences and similarities from their experiences. That could have made this mildly interesting doc much more compelling.

The filmmaking by directors James and Mack is solid but not golden. There were plenty of chances to impress audiences with camera angles, lighting, perspectives, dazzling assemblages of archival photos and production elements. Yet the footage (cinematographer Derek Wiesehahn), editing (Vito DeCandia and Brett Mason), sound (Andrew Berger and Mike Frank) and music (Lauren Denemark and Andrew Weaver) are just average. Never astonishing.

This nostalgic video photo album of Black students from Yale’s class of ‘97 had the potential for greatness. But it needed to dig deeper to get there. It needed to challenge opinions and create a lively debate about the social/racial issues that it skims.

For information about the Tribeca Film Festival go to: https://www.tribecafilm.com

Visit Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com.